Dive Site Conditions

In the Skills section you learned that a site assessment should be conducted as soon as you arrive at a dive site. This provides you with the opportunity to evaluate the site’s conditions and determine if they are favorable for diving.

No matter where you plan on diving, you must consider the site’s accessibility, visibility, temperature, currents, and bottom composition. Diving in the ocean presents additional factors such as waves and tides. Observing these conditions prior to a dive helps to prepare you to deal with them while in the water and avoid potentially hazardous areas of a dive site.

On this page, you’ll learn how to assess a site’s conditions, how they occur, and how to cope with them during a dive.

Tides

If you observe the ocean’s coastline for several hours, you’ll notice that the water level changes over time. These changes are called tides, and are the result of the gravitational pull of the moon, and to a smaller extent, the sun. In most areas of the world, the tidal changes are only a few feet, but depending on the geographic location, can be as much as 5 feet in either direction.

Tides affect divers by exposing or concealing rocks that are at or near the water’s surface. For example, a low tide may expose rocks that make the entry and exit hazardous, but when the tide rises, these rocks may be completely submerged and safe to swim over.

Tide charts are available that tell you the time of each day’s high and low tide, as well as the water level at each tide. These are available at many dive shops, and are also printed in most newspapers.

Swells

Most waves are caused by surface winds blowing along the surface of the ocean. Waves begin as small ripples on the surface, but if the wind continues or increases in force, these small ripples gradually increase in size and become swells.

Swells directly affect divers who are diving from a boat. Even the smallest swells will rock an anchored boat, making dive preparations, entries, and exits difficult. For this reason, most boat operators select dive sites that are sheltered from dominant swells.

Large swells can be extremely hazardous, so boat operators closely monitor weather conditions prior to each day’s charters. When swells are determined to be unsafe for travel, operators will cancel the day’s charters.

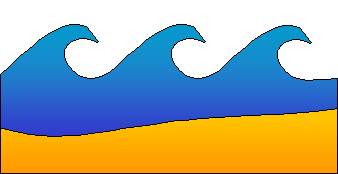

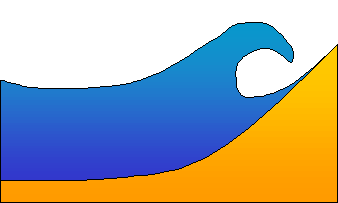

Surf

Surf forms when waves reach shallow water and slow down until they crash forward. Most shores are exposed to some form of surf, so if you plan on diving from the shore, you need to know how to judge surf conditions and plan an appropriate entry and exit.

Beaches with gentle slopes experience spilling breakers over a long distance. The area where surf breaks is called the surf zone, and can be difficult to pass through when waves are large or close together.

On steep beaches, the surf is more likely to break close to the edge of the water. These are called plunging breakers, and their surf zone is short in comparison to other types of surf. However, they are very powerful, and should be avoided unless they are small enough to make a safe passage.

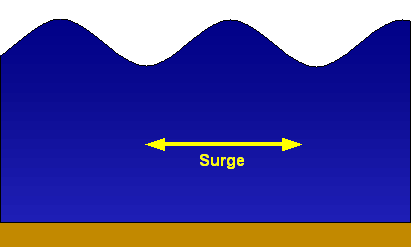

Surge

As waves pass overhead, they create a back-and-forth movement of water called surge. The effects of surge increase when waves are large, but also decrease as you increase your depth.

Strong surge is capable of moving your body back-and-forth while you’re underwater, and you’ll quickly discover that it’s nearly impossible to swim against it. To avoid overexertion, it’s best to rest as the surge pulls you back, then swim forward as the direction of the surge shifts to the direction you wish to swim.

Currents

Currents are best described as rivers or streams within a larger body of water. In the ocean, currents are formed by winds, waves, tides, and the rotation of the earth.

The largest currents in the ocean are offshore standing currents, which are a major factor in water temperature. For example, currents off the West Coast of the United States primarily move from the north to the south, which means the waters are chilled by the cold, northern waters. On the East Coast, currents move from the south to the north, which significantly increases the water temperatures.

As divers, we are more concerned about the currents that are present near the shore. These include longshore, rip, and tidal currents.

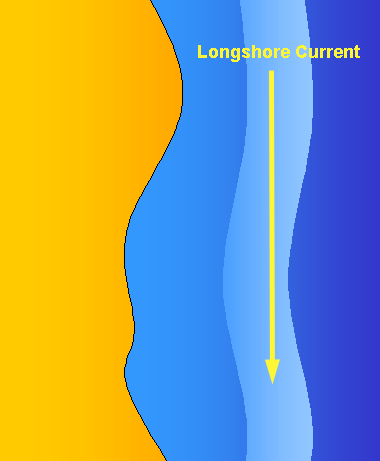

Longshore Currents

Longshore currents run parallel to shore. Like offshore currents, they are considered standing currents, which means they rarely change direction if ever at all.

Longshore currents can move you far from your entry or planned exit location. To avoid a long surface swim or losing your dive party, you must determine the direction and speed of the current and plan your dive accordingly.

There are several indicators that can help you determine the direction of a longshore current. One indicator is the direction from which waves approach shore. If the waves approach the shore from the south, the current is likely to come from the same direction. Another indicator is the direction anchored boats face. Most boats are anchored from their bow, so they face against the current.

Rip Currents

Rip currents move perpendicular to the shore, and are common at most beaches. These are transitory currents, which means they can suddenly appear without warning.

Rip currents form when backwash from surf is forced to travel back into the water through a narrow passage such as a reef or sandbar. They are identified by a stream of foam traveling away from the surf zone.

While rip currents can be too strong to swim against, they are also quite narrow in size. If you become caught by one while trying to swim to shore, the best response is to swim parallel to shore until you exit the current.

Some rip currents can be beneficial. If you are surface swimming to a dive site, a rip current can assist you during your swim and carry you closer to your destination.

Tidal Currents

Tidal currents form when incoming or outgoing tides force water through a narrow passage. Since tides move in and out several times a day, the direction and force of tidal currents changes throughout the day.

Currents of this type are often too strong to swim against, so careful planning is required before diving in areas with tidal currents. The safest diving is during slack tide, which is the period when tides are about to change direction.

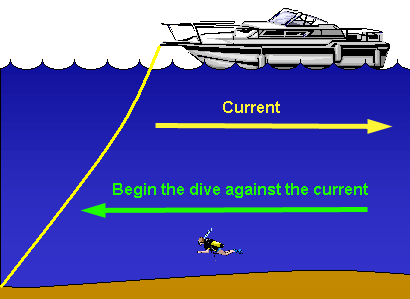

Diving in Currents

The direction and speed of currents are major factors to consider when planning your dive. Most dive plans require that you exit at or near your entry point. If you allow a current to carry you away from the boat, you may have to surface before you reach your exit location. This will require you to make a long surface swim against the current to make it back to your exit location.

The best approach to diving in a current is to begin your dive against the current. This allows you to turn around half-way through your dive, ride the current back to your exit location, and remain there until it’s time to surface.

When strong currents are present, a rope should be extended behind the boat. This is called a current line, and is used to pull yourself against the current and back to the boat.

Visibility

Visibility refers to the distance you are able to see while in the water. Several factors play a role in how much visibility there is at a particular site, and these can change from day to day.

One of the major factors is bottom composition. Fine sand, silt, and mud are easily stirred up into the water by currents and waves, so visibility is generally better at sites with rocky bottoms or coarse sand.

Visibility can also be reduced by heavy populations of microscopic plants and animals. These growths are often temporary, and can disappear after a few days.

Rivers, streams, and runoff from storms are other factors that reduce visibility. These waters carry sediments into the ocean, and result in murky waters.

Diving In Low Visibility

Divers in limited visibility must be careful to avoid losing each other, navigating off-course, and running into hazards such as sharp objects and fishing line. Diving in these conditions requires special skills and should not be attempted without proper training.

To avoid losing each other, buddies can either hold hands or hold onto opposite ends of a length of rope called a buddy line. Carrying lights is also beneficial because they make you more visible to other divers.

In extremely low visibility you may experience disorientation and lose your sense of where you are or which way is up. If you must dive in extremely low visibility, the best prevention against disorientation is to dive near vertical references such as an ascent line.

Climate and Water Temperature

Geographic location and local currents play a major role in a site’s average water temperature, but these temperatures can vary by 10º F or more as seasons change. For example, water temperatures in Hawaii are typically in the mid 80’s during the summer, but can drop to nearly 70 degrees during the winter.

Lakes are subject to severe changes in seasonal water temperature. Many lakes that are popular for water sports during the summer can actually freeze during the winter.

When planning a dive vacation, it’s important to check the region’s current water temperature so you can ensure you’ll have the appropriate exposure suit. Diving in inadequate thermal protection is uncomfortable and dangerous.

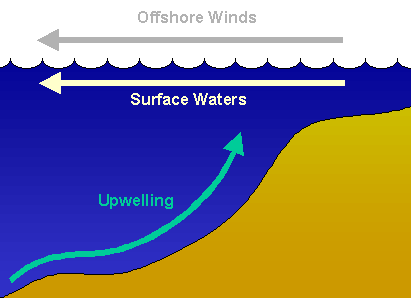

Upwelling

At some coasts, water temperatures are lowered by upwellings that carry deep, cold water up to the surface.

Upwellings occur when strong offshore winds blow out towards sea. As the surface water is pushed away from shore, cold water from the deep travels up to take its place. In addition to lowering temperatures, upwellings also increase both visibility and the nutrient content of the surface waters. This makes for excellent diving when upwellings are present.

Thermocline

Water temperature normally decreases with depth, but in some locations you may notice a sudden and drastic change as you descend. This is called a thermocline, and is common in fresh water lakes and on occasion, the ocean.

During the summer, thermoclines result in warmer surface waters and colder deep waters. Lakes can experience a reverse thermocline during the winter when the upper layer is colder than the deeper layer.

When diving an area known to have a thermocline, it’s important to wear the appropriate amount of thermal protection for the depth you plan to dive to. You can get information about local thermoclines from a local dive shop

Bottom Composition

A site’s bottom composition determines the life you’re likely to see and the visibility you can expect. Most dive sites feature bottoms that are composed of rock, gravel, sand, silt, or mud. In general, rock and gravel bottoms feature more life and better visibility. Sand, silt, and mud bottoms are easily stirred up into the water, and are populated by life forms that spend most of their time buried deep under the floor.

The best indicator of a site’s bottom composition is the composition of the nearby shore. If a shore consists of a wide, sandy beach, the same features are likely to continue underwater. On the other hand, rocky sites are more likely to be found off rocky shores.

Bottom Contours

The contours of a site have a dramatic effect on the site’s depth range and diversity of life. Like bottom composition, you can usually predict the contours of a site by observing the slope of the nearby coast.

Most divers prefer sites that feature steep or vertical bottoms because they host a wide variety of life. Flat sites may also be rich with life, but you’re not likely to see much diversity from one location to the other.

When diving steep sites, it’s important to watch your depth carefully to avoid descending below your maximum planned depth. The best dive plan in these environments is to begin your dive at your deepest planned depth, and work your way up to shallower water during the dive.